Decolonising development: power dynamics in the knowledge sector

This blog was originally prepared by Emily Hayter, INASP Evidence-Informed Policy Making Team Programme Manager, as a think piece for the online global conference Decolonising development: Whose Voice, Whose Agenda? organized by Leeds University Centre for Global Development and INTRAC.

Who sets priorities for research? How can we ensure research evidence is considered as part of policy making?

At INASP we focus on strengthening national research and knowledge systems in developing countries. Recognizing that much of the most influential research in and about these countries is funded and/or led from and/or published in the global North, we work specifically with Southern researchers and research systems to amplify their contribution to framing and addressing development issues. This means supporting the production, sharing and use of Southern research.

What does a ‘research to policy’ system look like?

In our view, it is made up of multiple ‘suppliers’ and ‘demanders’ of research. This includes civil society organizations, universities, think tanks, the media, government ministries and departments, parliaments, donors, coalitions, the private sector and others. All are producing, sharing and using research and other forms of knowledge in different ways to inform policy and practice. We work with partners across this system, in more than 25 countries around the world. Knowledge production and use is a deeply politicized space and there are many different regional, linguistic, racial, religious and gendered power dynamics at work in our sector.

Who decides what counts as evidence for policy?

Ultimately, it’s the decision makers themselves who shape what knowledge is used and how. Here are three things we’ve learned from working from what is often called the ‘demand side’:

- Recognize that research is not the only thing that feeds into policy—nor should it be. Policy making is a political and representative process. The tension between representing citizens’ views and following guidance from research is the subject of debate and headlines around the world, particularly at the moment. Evidence is only one thing that informs policy, alongside a host of other factors such as budgetary constraints and political realities.

- Evidence is not what you think. Ask a researcher what evidence is, and they’ll likely talk about methodological rigour, randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews. Ask a policymaker, and they’ll tell you about talking to a head teacher at a local school, or inviting an expert to testify before a committee. In order to see research feed meaningfully into policy in developing countries, we need to understand how policymakers in these countries view evidence and what their needs are. Our Evidence-Informed Policy Making Toolkit aims to contribute to this, in part by focusing on four types of evidence used for policy: statistical and administrative data, citizen knowledge, practical experience, and (last but not least) research.

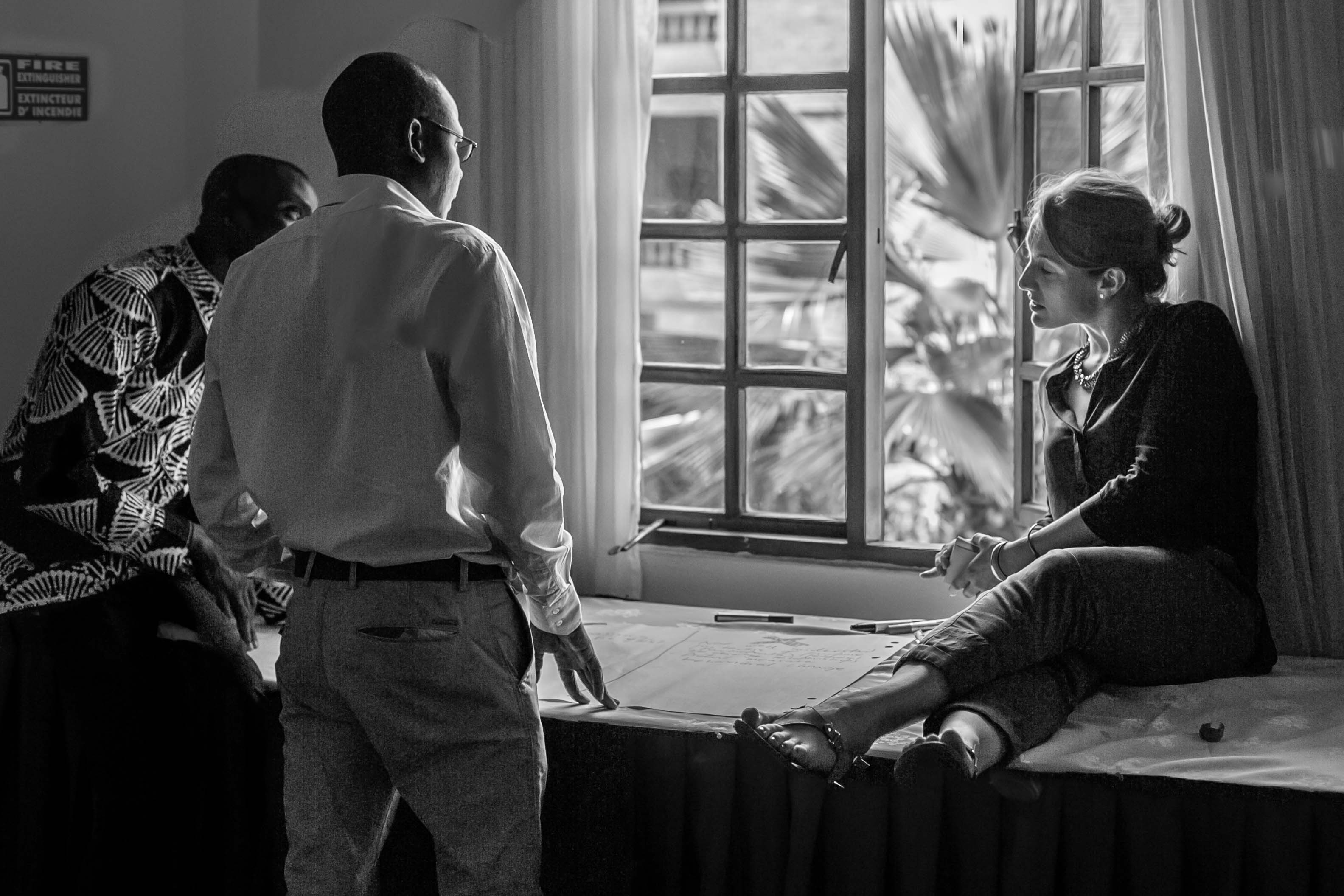

- Relationships are crucial. Sustainable relationships between researchers and policymakers are fundamental to enabling co-creation: opportunities for researchers and policymakers to jointly define problems and shape research agendas and questions. These are often informal which means they are difficult to concretise and measure. But without them, we won’t see research systematically considered in policy. Two successful examples of what this looks like in practice are:

- Parliament of Uganda’s Research Week, which brought 18 leading research institutions to Parliament, reaching 242 Members of Parliament (MPs) and 107 members of staff to showcase the research being done in Uganda and discuss how to strengthen informed debate in Parliament. This has resulted in increased requests for research from MPs, as well as strengthened formal and informal relationships between Parliament and the national research sector.

- The African Centre for Technology Studies’ Climate Change Round Tables in Kenya brought together policymakers and leading Kenyan scientists as part of an effort to strengthen the evidence base feeding into the country’s Climate Change Bill. This had been approved by Parliament but denied Presidential Assent due to a lack of sufficient stakeholder input. The Climate Change Bill was subsequently passed.

Power and voice

There are a number of power dynamics that continue to affect this. Working in development means we are negotiating and reflecting on these issues constantly in our day-to-day work.

- What if national policy decisions aren’t made in the national policy system? Despite aid effectiveness reforms which initially seemed to prioritize country ownership, in aid-dependent countries decisions about national policy content continue to be heavily influenced by donors and multilaterals. This means ‘decision makers’ might just as likely be in Brussels or Washington as in Nairobi or Accra.

- How to strengthen the role of Southern research Most international development research continues to be funded from the North and published in the North. As my colleague Jon Harle notes, “research that asks somebody else’s questions is likely to lead to a mismatch between national development agendas and research which might support these”.

- How to ensure that policymaker-researcher discussions are inclusive and diverse Even when meaningful spaces of co-creation emerge between researchers and policymakers, there are other kinds of inequality and marginalization at work in those spaces. For example, just 28% of researchers worldwide are female. And most of the parliamentary staff and civil servants we’ve worked with recently in Zimbabwe, Uganda and Ghana are male.

- How can we in Northern international development organizations be more self reflective about our own diversity and power dynamics? At INASP we are going through a gender audit which has helped us begin reflect more on the power dynamics at play in the way we work. I hope we can continue to explore this and other forms of power and diversity in our organization.

How do you negotiate power dyamics to decolonize development in your work? Let us know in the comments below.

INASP works to strengthen the production, sharing and use of research for national development in over 25 countries worldwide.

Interesting in hearing more? On 28 June we are hosting a seminar in Oxford on Co-creation, capacity development and policy engagement. It will be an opportunity to discuss some of these issues in more depth, to share ideas and experiences. We welcome research leads, PIs and research coordinators who want to do something different as they approach new funding calls such as the GCRF. For more details visit www.inasp.info/seminar

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post