The right to health: policymakers and evidence for HIV prevention

Emily Hayter, Programme Manager, Evidence-Informed Policy Making at INASP, and Josee Koch, Technical Lead, Evidence into Practice, EHPSA Programme (Mott MacDonald)

“The right to health” is this year’s theme for World AIDS Day. This brings together a focus on public health and a focus on human rights—quite controversial when we are talking about key and vulnerable populations and HIV prevention.

We apply various forms of evidence to navigate controversy. Evidence is sometimes regarded as a neutral player in the game, presenting scientific facts and logic without favouring a specific policy outcome. But, as we know, for HIV prevention for key and vulnerable populations, the picture is a lot more complicated.

Of course, evidence plays a critical role in designing and implementing the most effective and efficient HIV prevention policies and programmes and saving lives. But in HIV prevention policy, the topic of evidence involves many points of debate, from what constitutes ‘good’ evidence to how to negotiate the intersection between health and rights. So how can researchers effectively contribute to the policymaking process in such a controversial area?

The Evidence for HIV Prevention in Southern Africa (EHPSA) programme recently collaborated with INASP to explore this question. We wanted to understand evidence use for HIV prevention policy for three key and vulnerable populations: men who have sex with men (MSM), prisoners, and adolescents. Here’s what we learned:

How do policymakers and influencers like to receive evidence?

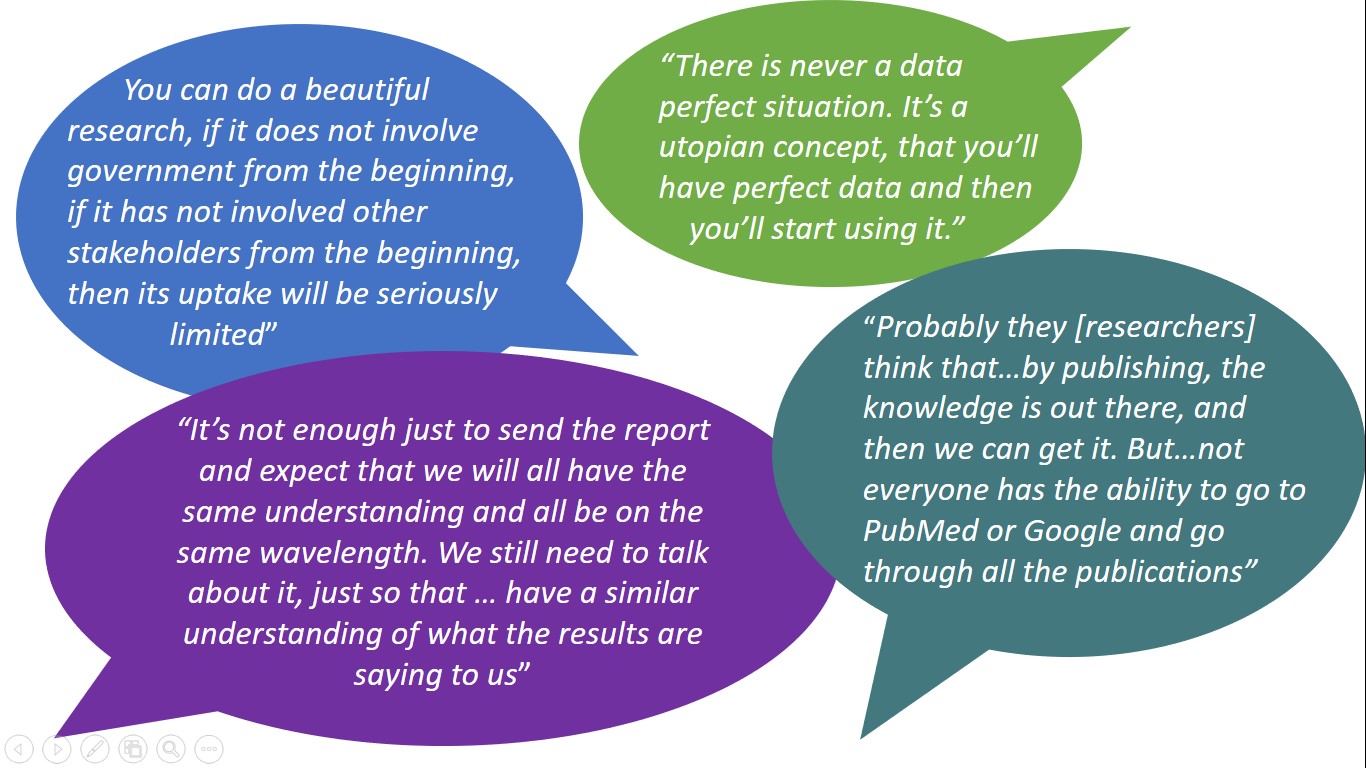

We spoke to EHPSA stakeholders in eastern and southern Africa to find out how they like to receive evidence. They shared lots of practical insights:

- Face-to-face engagement is key…. Policymakers like to receive evidence in face-to-face meetings, such as through conferences, Technical Working Groups, and other multi-stakeholder spaces. And they want a two-way engagement that

allows collaborative interpretation and discussion of results with researchers, not just a presentation telling them what to do.

allows collaborative interpretation and discussion of results with researchers, not just a presentation telling them what to do. - …and it’s not a one-off event. Policymakers generally prefer a series of engagements and dialogues over the duration of a period of research. They want to be consulted from the beginning of the research process, involved in shaping the questions and interpreting the findings—not only informed of the results at the end.

- Clear and compelling outputs: The two outputs which policymakers told us are most useful are policy briefs and PowerPoint presentations. These should be clear, brief, jargon-free, and ideally provided alongside face-to-face interactions.

- The ‘messenger’ matters…Policymakers showed great sensitivity to the approach of individuals who present research results. National or regional presenters were generally preferred over international presenters—several interviewees pointed to the importance of peer learning and the influence of regional ‘champions’ for certain issues. The tone and demeanour of the presenter is also important, as the discussion should be framed as an invitation to dialo

gue rather than a one-directional lecture.

gue rather than a one-directional lecture. - …as does the message. Messaging around HIV prevention for key populations is particularly challenging and sensitive. To have maximum impact, our respondents told us messages should be clear and practical—this may involve specific training or sensitisation around messaging, as there’s a high risk of misinterpretation of results. They also suggested that for some populations such as MSM, messages initially framed around health can act as a stepping stone to future discussions around rights.

Collaborative responses are needed

Researchers hoping to navigate the complex policy-making area of public health and rights therefore need to be strategic about engagement—the message and the messengers matter.

The risks of not taking this seriously are signif icant. Our review found plenty of examples where poorly handled engagement and messaging around health evidence had led to dangerous misinterpretation of results and damaged relationships—not only for the research team involved, but for future researchers as well. Long-term, two-way dialogue and thoughtful, politically informed messaging are the most promising ways to lay the groundwork for uptake.

icant. Our review found plenty of examples where poorly handled engagement and messaging around health evidence had led to dangerous misinterpretation of results and damaged relationships—not only for the research team involved, but for future researchers as well. Long-term, two-way dialogue and thoughtful, politically informed messaging are the most promising ways to lay the groundwork for uptake.

Neither researchers nor policymakers can achieve right to health for vulnerable and key populations alone. A collaborative response is needed. This World AIDS Day, we celebrate the role of evidence in informing approaches to realise the right to health, and we look forward to supporting dialogue on these issues between researchers and policymakers in the year to come.

look forward to supporting dialogue on these issues between researchers and policymakers in the year to come.

These findings are the result of a brief critical review commissioned by EHPSA and carried out by INASP, to understand the factors shaping policymakers and policy influencers’ demand for HIV prevention evidence in eastern and southern Africa. The project aimed to show how policymakers and influencers currently consume evidence, and identify opportunities for uptake of evidence from EHPSA’s studies.

Additional reading on this topic including an infographic, evidence brief and summary report are all available on the EHPSA website.

INASP is an international development organization working to support research and knowledge systems in 28 countries. INASP’s Evidence-Informed Policy Making team works with public institutions to strengthen capacity for the systematic use of a wide range of evidence in policy making. www.inasp.info @INASPinfo

The EHPSA programme supports an effective and efficient HIV prevention response in eastern and southern Africa. EHPSA is funded by UK aid from the Department for International Development and managed by Mott MacDonald. www.ehpsa.org @EHPSAprog

This article was first published on the EHSPA blog.

Next Post

Next Post