Digital learning isn’t good for equity – or is it?

Joanna Wild & Jon Harle – Photo: Kamaldeen Olal

There is a consensus that digital learning isn’t equally accessible to all sections of society in the South, and that its primary users – and thus those who benefit most – tend to be highly educated men based in urban areas, and in countries where the technological infrastructure and connectivity is more advanced.

In this blog we explore equity as it relates to women. The literature indicates that structural “offline” barriers limit their access – such as caring responsibilities, or the ability to travel to access good connections.

Read on for more ideas about how to design with gender in mind, and join us on 16th May to hear our expert panel discuss the question: how can gender-responsive pedagogy inform the design of online courses?

Women are more likely to complete an online course

In INASP’s digital work, women have generally been only slightly under-represented – that’s significant, because the gender gap is usually bigger for in-person courses and events. Women typically represent around 4 in 10 participants in our digital initiatives, although it varies: in a course for journal editors, women represented only 37% of participants (no doubt reflecting the profile of editors of academic journals), while for a course on research writing for Latin American participants, they represented over 50%.

But what’s more interesting is that, once they start a course, women are more likely to complete it than men. It’s a marginal difference – between 49% and 72%, compared to 47-68% for men – but it’s significant, nonetheless.

This also applies to courses that our partners have gone on to run themselves: in 2017, Thai Nguyen University (TNU) in Vietnam adapted and ran an INASP course; 69% of those who started the course were women, and 77% of those who completed it were women.

And looking at over 3,000 people who participated in one of INASP’s MOOCs, women’s confidence levels increased slightly more than those for men. Perhaps that’s because men tend to start out more with greater confidence in what they already know, but it’s still a result worth noting.

Can digital learning help to overcome structural barriers?

What these figures don’t suggest, of course, is that more women are accessing online learning, and succeeding or benefiting through online learning, than men. What they do suggest is that there’s a slightly more positive picture emerging from INASP’s work – and that gives us reason to think that digital learning could offer new possibilities for women to develop skills and confidence that can help to overcome some of the deeper, structural barriers that they encounter.

Anecdotally, we’ve heard that online learning can be easier to access if that access isn’t controlled by institutional gatekeepers in the same way as in-person training might be. It might also be easier to fit around family and caring responsibilities.

We need to tackle the structural impediments for women – in research and knowledge systems and in society as a whole – and digital is certainly no panacea. But digital learning might have a part to play in strategies for change.

Designing for equity

So how can we design for digital experiences that help to improve equity?

The simple answer is by starting with the needs of the learners and using those to guide you. That means a design team that is put together with an explicit concern to mitigate bias –a team which has a good gender balance, and which understands what equity means in a design context. How might biases be encoded in the materials used, or the language of a course? What do we need to do to ensure learning spaces – the virtual classrooms and spaces – are inclusive and safe places? Having at least one member who can review the design from a gender perspective will help, but everyone involved in design and facilitation has a part to play.

Gender responsive pedagogy

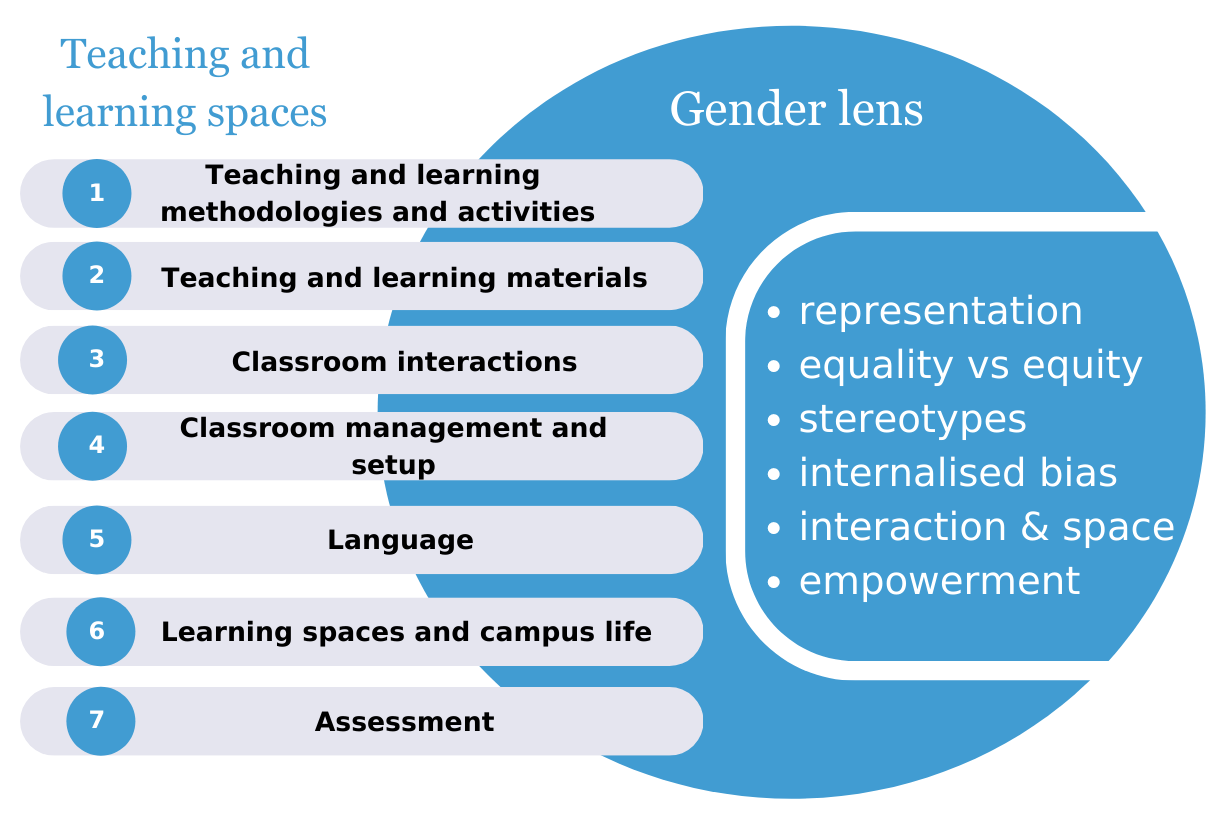

We are also guided by a framework for gender-responsive pedagogy, that we developed with East African partners. The framework takes six dimensions important for gender-responsive teaching (representation, equality vs equity, stereotypes, internalised bias, interaction and space, and empowerment) and applies these to seven teaching and learning spaces, ranging from classroom activities, to teaching materials, to assessment strategies.

Originally developed to guide the design of in-person classroom teaching, we observed a 50% increase in lecturers who ‘very often’ or ‘always’ organised their classrooms to be gender responsive, a 40% increase in development of gender-responsive teaching and learning materials and a 35% increase in lecturers who guide the use of appropriate gender-responsive language in class. Building on this, we have delivered an online programme for university educators in Ghana and Nigeria and are currently developing a set of criteria for gender-responsive pedagogy in online course design and delivery.

Join us on 16th May to discuss these questions further

On 16th May at 12.00 BST we’ll be picking up these questions with colleagues from Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda. Joining us will be Dr Nicola Pallitt, from the Centre for Higher Education Research, Teaching and Learning, Rhodes University, South Africa, Dr Funmilayo Doherty, from Yaba College of Technology, Lagos, Nigeria, and Dr Albert Luswata, Uganda Martyrs University, Uganda.

We’ll be asking them about their experiences of designing and leading online learning programmes, and how they have grappled with these issues as they did so.

Watch the webinar recording here: How can gender-responsive pedagogy inform the design of online courses?

You can read more about these themes and about good learning design in Part 3 of our new book Digital Technology in Capacity Development: Enabling Learning and Supporting Change.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post