MOOCs and educational development: Part 2

This is the second in a series of blog posts on MOOCs (massive open online courses).

Early in 2012, MIT announced its first MOOC. This was about electrical circuits. My academic background is in electrical engineering, so I was inspired to sign up and take a look. The first lecture was a lesson in humility. I realized I knew very little in spite of having a master’s degree in the discipline. I worked as a traditional engineer only for a few months after my studies and many years had passed since then, so I consoled myself after dropping out. It was MIT material, after all. Maybe there would be a more suitable MOOC for me later on.

In October 2012, I came across a tweet about an edX course in biostatistics and epidemiology, offered by Harvard University. The full title of the course was “PH207x Health in Numbers: Quantitative Methods in Clinical & Public Health Research.” I was looking to learn about statistics, and my work in life sciences editing and teaching scientific writing had given me an appetite for learning about the health sciences in a formal way. And the Harvard part was definitely a magnet.

The course was to start that day, and I signed up. It was going to be a 12-week course, and students were expected to spend about 10 hours a week on it. The course seemed interesting enough, but I doubted whether I would be able to spend that much time every week for nearly 3 months. I had just relocated to Mumbai and was settling into a new work routine.

The topics covered in the first 3 weeks were not difficult: basic statistics, probability, an introduction to Stata (a software application for statistical analysis), and concepts of prevalence and incidence. Every week, I watched a series of lectures given by two professors, Marcello Pagano and Fran Cook, both from the Harvard School of Public Health.

Here are a couple of screenshots from the lectures:

The monitor in the first image allowed handwritten input from a marker, which was overlaid on the slide text. The teachers would regularly walk to it and emphasize or write something. The second image shows this more clearly. The video had a number of options, such as turning on captions (a transcript of the speech), playing in HD (I didn’t use this – the regular mode was good enough), and changing the speed (0.75x, 1x, 1.25x, and 1.5x). For me 1.25x worked best, and I imagine 0.75x might have been good for people with English as a foreign language.

The videos were hosted on YouTube, so the server-side bandwidth couldn’t be faulted. But this is a topic for a later post.

Coming back to the nature of the videos, these were not made during classroom teaching. They were made for the MOOC. With the professor facing the camera, the excellent video-editing (showing close-up shots of the slides at key moments), the video controls (pausing, speed varying, captions), the experience was far better than sitting in a classroom. I’ll hasten to add that I’m not talking about small-group, discussion-oriented classes, but about large-group, lecture-driven classes. But really, how many people have the privilege of going through university education with most classes in the first format?

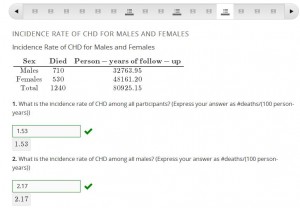

There were two kinds of continuous assessment: questions in between lectures, and weekly quizzes. Because of the quantitative and objective nature of the course material, all the questions were of the multiple-choice or fill in the blanks format.

The above screenshot shows a set of questions in between lectures (see the top bar which gives an idea of the mix of lecture videos and questions). Students could attempt these questions as many times as they wished until they got the answer right. But each quiz question could be attempted at most 10 times. I found this limit quite generous, except in a few cases where I just couldn’t figure out how to solve a problem and I found myself making wild guesses after a few attempts.

The course was a riveting experience the very first week. I met the weekly deadlines for quizzes for 3 weeks and did well. Then the material started becoming a little challenging. I began to worry. Twelve weeks seemed awfully long. I was going to take a 2-week vacation in December, and the course was to end in mid-January. And there was going to be a final exam worth 60% of the grade! Could I keep up?

To be continued…