Exploring political economy analysis at INASP

In the first of two blog posts, Emily Hayter discusses how INASP is using context analysis to help inform our programmes, and why this is important.

INASP’s work is founded on the belief that knowledge systems are strongly affected by power dynamics, both between north and south and within the southern contexts that we work in. Understanding the political context of our work and actively using this information to inform our programming is therefore critical to our work as practitioners. In recent years, INASP has been moving towards a more adaptive management model within our programming, with greater scope and opportunity to apply context analysis than a traditional, linear model of project management.

In this post, we share the context analysis approach developed by our programme team to help us get to grips with political economy analysis (PEA), a structured approach to examining power dynamics and economic and social forces that influence development.

As The Policy Practice put it, “everyone agrees that understanding the politics is important now”. But, while some of our programmes work directly with governments, most of our work is with stakeholders that might be seen as less obviously ‘political’. These include universities, research institutions, academic journal editors, and libraries. Our work is usually not funded through donors’ governance departments, but through their research or education department.

Our PEA journey began with asking how we can build PEA analysis systematically in ourprogramme work?

We set out to understand more about PEA, through taking the ODI-Policy Practice PEA course and setting up conversations with colleagues in the sector. While these helped us build a picture of PEA and how it had evolved from a one-off piece of analysis to an integrated ‘thinking and working politically’ model, it also revealed some gaps. We had hoped to find out more about how other small NGOs were approaching PEA. However, we were daunted to find very few examples that weren’t from large INGOs, consultancy firms working on governance projects, multilaterals or donors. As practitioners, we also wanted to know more about the practical, operational details involved in ‘thinking and working politically’, but again we didn’t find much.

We needed to come up with a model of PEA that:

- Has a spectrum of different tiers or options which we could use for a variety of projects, since our work varies from six to eight months to five years.

- Be implementable internally (particularly for smaller projects), without having to contract consultants.

- Be applicable to the knowledge and evidence systems focus of our work, while also incorporating a gender and equity lens (a major focus of our strategy).

- Point to practical, tangible everyday actions that we can integrate into our routine work.

We set out to pilot the first stages of a PEA a couple of years ago in some very different INASP projects: Strong and Equitable Research and Knowledge systems in the Global South (SERKS) and Transforming Employability for Social Change in East Africa (TESCEA), as well as the Assuring Quality Higher Education in Sierra Leone (AQHEd-SL) partnership in which we play a small role. Although these projects were at the inception stage, SERKS was an exploratory project, with a somewhat flexible timeline. In contrast, TESCEA was already planned and underway, with the typical rush to get things done in the implementation period and not a lot of time to step back and think.

Our approach here was to start learning by doing, trying a few different approaches to start a conversation among our programme team about how PEA can inform real-world project decisions, rather than to focus on creating an exhaustive, in-depth research report that might just remain on our desks.

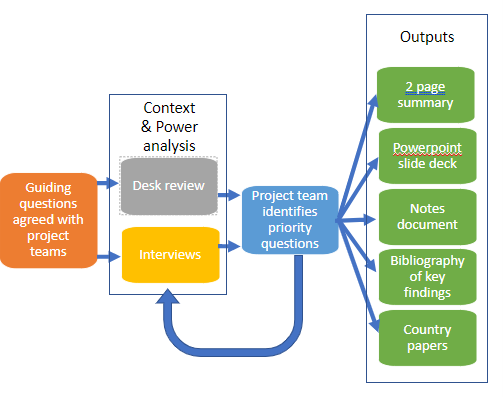

We based our approach on classic PEA levels of analysis (foundational factors; actors and agents; rules of the game), but shaped guiding questions with project teams. After each stage was complete, we met with project teams and identified priority questions for the next stage. This helped ensure that the analysis continued to answer live project questions.

Undertaking PEA alongside project delivery meant that the analysis took quite a long time (eight to nine months), as we waited for project teams to identify priorities and outputs before moving from each stage to the next, respecting their timescale and decision points. As we had not done PEA before, there also wasn’t always clarity on who within the project team should make these decisions.

We tried different depths of analysis at the same time. The projects covered a range of focus countries between them. For countries common to both SERKS and TESCEA (Uganda and Tanzania), we undertook in-depth analysis incorporating the slightly different lenses of each project. We also added in extra layers of analysis as the need arose, incorporating what we called a ‘micro’ or organisational level lens to better understand the internal structures and systems of the institutions we were partnering with as well as how they fit into the wider research system in these countries. This in-depth approach was complemented with more rapid and less in-depth context analysis in countries specific just to SERKS – Ethiopia, Bangladesh and Sierra Leone (where our connection is largely through the AQHEd-SL partnership).

We produced a range of smaller outputs instead of one full PEA report for each country. From the beginning, we knew that the classic lengthy PEA report was not the best way for our colleagues to digest the insights we were gathering. Instead of a report, we produced a series of short outputs for each country:

- A two-page summary of key foundational factors, a snapshot of the current political climate, a diagram of main national development planning structures, and key points on actors, agents and issues in our sectors of interest (youth skills and employability and the research system).

- A PowerPoint slide deck organised by the three levels of PEA (foundational factors; actors and agents; rules of the game).

- A lengthy and detailed notes document, organised by guiding questions and containing a table of contents and references.

- A bibliography of key readings.

- Two short thematic papers (three to five pages) for each country, answering specific questions posed by the project teams.

We relied mainly on desk research. During the development of our pilot, we were mindful of the need to think carefully about making demands of our partners alongside busy project implementation schedules. As a result, our schedules allowed for interviews to be undertaken in Uganda, but not in Tanzania. For the most part, we used desk research to explore the three classic levels of PEA: foundational factors, rules of the game, actors and agents. We are keen to find ways of working more closely with partners on context analyses, as we share in the second part of this blog mini-series next week.

Everyone got stuck in. We took a very decentralised approach. Led by a PEA focal person, seven different members of the programme team were involved in reading and producing outputs. We also involved communication and monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) colleagues in feeding back on emerging findings and shaping priority questions, as well as wider project teams. This participatory approach supported a collective learning experience and helped us develop a richer understanding of the shared effort required to embed and act on findings throughout the project delivery. However, it also meant that the analysis was not as tightly controlled or focused from a research perspective as it could have been if it was carried out in a less participatory and iterative way.

How are we taking our model forward?

Once the pilot phase was completed, we held a workshop to reflect on what we had learned and what kind of contextual analysis model we wanted to adopt across our programmes. This resulted in an organisational context analysis model that is now called ‘Context and Power Analysis’.

We have developed an internal guide for our programme team on how to do it, and ensured that it is linked to other INASP analytical framings such as adaptive management, gender analysis, and our organisational strategy.

We also scheduled started planning a learning session where we hope to hear from southern partners in the SEDI and DAP projects who have been involved in PEAs, to learn from their experience. At the project level, each of the projects we piloted with took their own approach to taking forward the model we’d started. In our next post, we will reflect on the wider lessons from our PEA pilot.

Thank you to INASP colleagues Mai Skovgaard, Alex Barrett and Verity Warne for their contributions to this blog post.

Cover photo by Hugo Ramos on Unsplash

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post