Three things we have learned about political economy analysis – and some unanswered questions

Our last blog post described the pilot of a Political Economy Analysis (PEA) model for our work at INASP. In the second of this two-part series, we reflect on what we have learned, the challenges we faced and questions we are asking ourselves as we continue to integrate PEA into our project work.

Three things we have learned about Political Economy Analysis:

The principles of research uptake apply! Throughout the pilot, we were reminded of the importance of co-defining guiding questions with the eventual users (the project teams); the value of discussing emerging implications, not only final findings; the difficulty of aligning research processes to users’ schedules to find the right timing to do the analysis and to have it taken up; and the importance of being clear about how we hoped it would be used. As an organisation interested in research uptake, it was a good reminder to see these principles at work on a micro level within our own organisation.

PEA doesn’t have to be an in-depth research project to provide useful insights. Our PEA pilot covered five different countries and with varying depths of analysis. Interestingly, colleagues who worked on the ‘light touch’ analyses seemed to find this just as useful as those who worked on more in-depth analysis. In both cases, knowing what questions to ask, or what types of issues might be in the background, helped us have better conversations with our partners and other stakeholders on the ground.

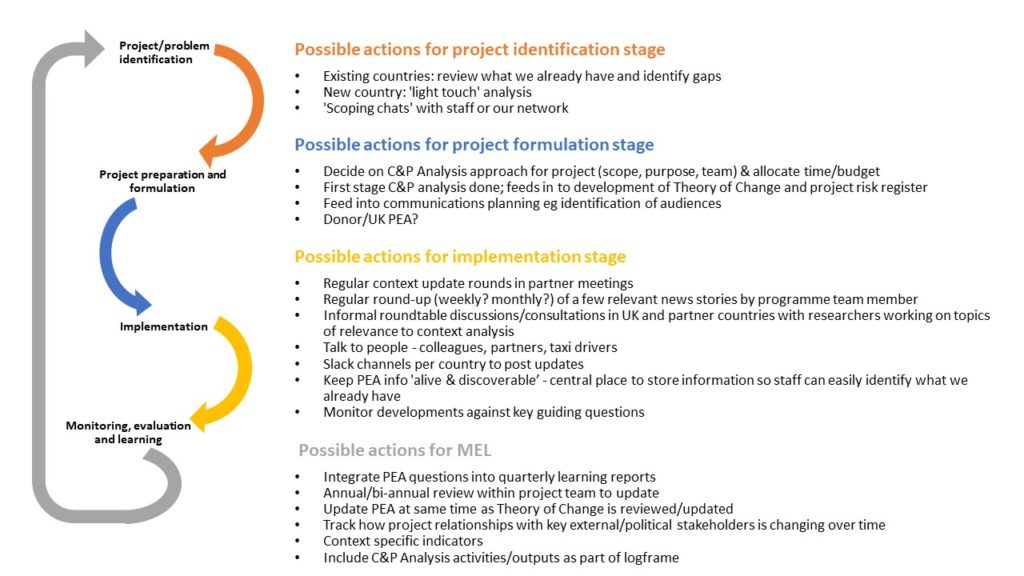

Even ‘applied’ PEA needs to be more practical. We like the idea of applied PEA as a form of ‘living analysis’ that gets updated regularly and feeds into the programme via adaptive management feedback loops. The sticking point for us was operationalising PEA findings—and we know others share this challenge – as Graham Teskey has pointed out on Duncan Green’s Poverty to Practice blog. Our decision to avoid a formal PEA report pushed us harder to integrate the analysis within our work. Programme colleagues report that doing the analysis early on in the project lifecycle supported a better understanding of project risks and sensitivities. For example, this meant a more nuanced picture emerging in our risk register in one project, and some careful framing of workshops in another project to work around sensitivities that had emerged from the context analysis. Project members also felt that undertaking background reading and analysis helped them better understand the ongoing context updates presented by partners in regular project meetings.

We have identified some specific ‘plugin points’ for PEA at different points of the programme cycle.

Still more to learn about how ‘thinking and working politically’ happens in practice

As we continue to integrate context analysis into our work, we continue to work through some questions:

Who is PEA really for? PEA is often used by outsiders (ie those in the north) to understand southern contexts—and this puts it at risk of the kinds of skewed north-south research dynamics that INASP is dedicated to countering. While there is always value in thinking about political interests and stakeholders, we are keen to learn what changes when the PEA is led by an actor embedded within the context rather than outside it? Context analysis is something we would rather do with our partners than about them—and while we know it’s something partners would like us to improve on, there’s still some exploration to be done to understand how this could work best.

Could we undertake PEA as a joint partnership exercise? For example, a joint UK-Ugandan team conducting PEAs to understand how the context in both countries might affect our work (recognising the influence that the UK political and governance landscape has on UK-funded international development projects).

Who can and who should do PEA? Is PEA something you need to contract an expert to do, or can it be done by programme staff? Like others, we think it is possible and useful for programme staff to do some level of context analysis ourselves, but we still have some questions about how this works in practice. How can or should it be done by NGOs who are not working on ‘governance issues’ but whose work is nevertheless intertwined with politics and power dynamics? What skills are needed for doing a PEA?

How does PEA work alongside our ambitions of partnership with government agencies, of co-design and co-identification of problems? How do projects that are working in partnership with government agencies conduct independent/rigorous PEAs? This is a very real question that has come up in our work recently. If PEA is a piece of extractive analysis that is done separately by a project team and is not shared or endorsed by the government agency the project is partnering with, what does that mean for building the kind of trusted relationships that are needed for effective institutional reform? How can PEA be something projects do with government partners rather than to them?

How can context analysis be integrated into projects that don’t have a dedicated PEA budget or plan from the start? This has been one of our biggest challenges. While we were able to use a degree of flexibility to carve out the time for an initial pilot, taking it forward has been a challenge for some projects—especially where it would have been an ‘add on’ in an already packed workplan, where every level of activity and detail is agreed in advance with donors, partners and fund managers.

We strongly believe that context analysis should be planned and budgeted for from the start—and in many cases, proposals ask applicants to demonstrate their understanding of the content. But the reality in many development projects is that time and budget to do ongoing context monitoring is not built in throughout the life of the project—especially in projects that are not seen as ‘governance’ focused.

Sometimes, the procurement and contracting stage can take so long that there isn’t time for context analysis at the beginning, and by the time implementation starts it is already behind schedule.

How exactlydoes applied PEA feed into project delivery? Even with dedicated time and budget,there is room for PEA models to engage much more closely with the operational ‘nuts and bolts’ of how development work is done—the key documents, plans, decision points and working models of development projects. In many cases it is procurement regulations, budget models, and reporting systems that are the real barriers to working politically—not a lack of interest on the part of programme teams. These aspects, often dismissed as ‘administrative’ or ‘operational’, are enormously influential in shaping our work. Without engaging with these aspects, it’s hard to see how projects can move from a ‘thinking’ toactually ‘working’politically. Developing more monitoring and adaptation capacity in implementation teams (rather than having MEL as a siloed, parallel function) is certainly part of the issue and could help to share accountability for internal learning. But this still doesn’t answer the question of where the task of monitoring and responding to the political economy context should sit in a project.

Where to from here?

In recent months, we have been monitoring the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on research and knowledge systems in the global south; and we have also conducted a short ‘refresh’ exercise on the focus countries in our pilot PEA. Based on these, we have set aside time and resource where possible in our 2021 workplans and budgets to continue to monitor and respond to the external contexts we are working in.

Our thinking on how to integrate context analysis into our programming design and delivery continues to evolve – and we look forward to sharing our learnings as it emerges. In the meantime, we would especially love to hear from other small NGOs who may be going through the same process!

Thank you to INASP colleagues Mai Skovgaard, Alex Barrett and Verity Warne for their contributions to this blog post.

Cover photo by Ninno JackJr on Unsplash

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post