Online learning: five ingredients of success

For more than five years, online learning has been an integral part of INASP’s capacity development approaches. Joanna Wild has previously reflected on the role of technology in capacity development and how we go about learning design. In this post, she shares some key ingredients for success.

Online and blended learning are important components of INASP’s approaches to capacity development as we seek to support more equitable knowledge ecosystems to put research and knowledge at the heart of development.

For the past five years of delivering a range of online and blended courses, we have been learning and systematically collecting feedback from our interventions. This has helped us to identify key ingredients for success in using online and blended interventions to support capacity development.

Some of these ingredients are design considerations that are needed at project conceptualization phase to help define what kind of intervention is most appropriate. Others come in later at the course design level and guide specific design decisions around the choice of tools, pedagogy, means and levels of support.

In this post we focus on five key ingredients of success:

- Meeting people where they are

Successful online courses begin by recognizing what participants need and what motivates them to take – and to complete – an online course. What is the added value of using technology from the learner perspective? How will it benefit them and allow them to accomplish things that wouldn’t be possible otherwise?

In answering these questions, it’s important to consider relevance to workplace role and/or studies; making sure that learning is at an appropriate level; and opportunities for accreditation. Most importantly, it involves continuity of learning – an opportunity for the learners to follow a coherent learning pathway rather than being exposed to one-off, disjointed training opportunities.

Finally, it is also important to understand the language and cultural context of participants. At INASP we are careful to use plain English in online courses and have run courses in other languages.

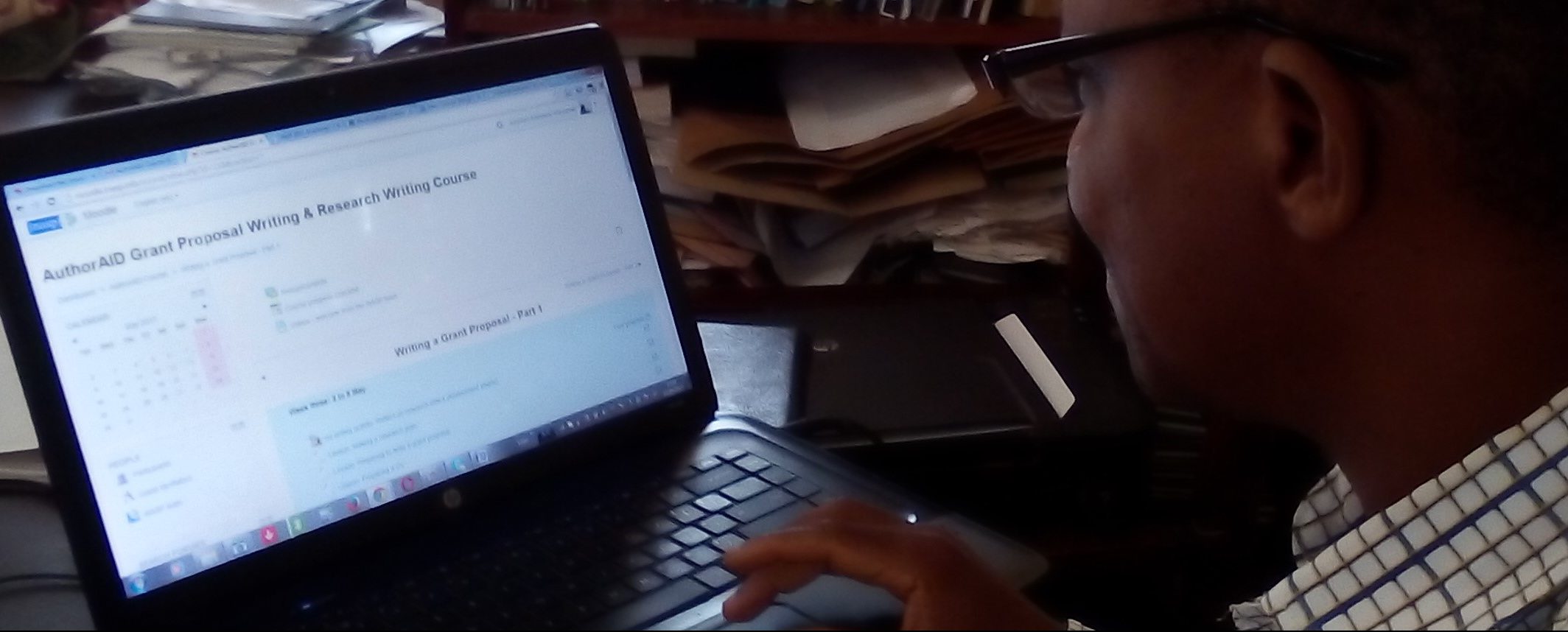

- Making the most of technology but recognizing constraints

As we try to meet people where they are, it is important to recognize the experiences and familiarity of participants to different technologies in designing an online experience. When we began offering online courses, we decided on the Moodle platform in the spirit of using open-source approaches but also because Moodle was already used in low- and middle-income countries. As many of our course participants are already familiar with the platform, they are able to focus fully on learning, instead of having to grapple with the technical aspects of the course. This remains a key criterion in how we choose digital platforms and tools to support learning.

Related to familiarity and experiences with online platforms is the flexibility to cater for low-bandwidth situations. The choice of technology at INASP is always made with equitable access in  mind, and we also provide offline digital learning opportunities – not only important for times when internet connection is poor but also for researchers who are studying while out in the field.

mind, and we also provide offline digital learning opportunities – not only important for times when internet connection is poor but also for researchers who are studying while out in the field.

However, we do recognize that many partners have increasing access to technology and that this can enrich the experience for participants, including for some with accessibility issues. We are therefore bringing more media (particularly video and audio) into our online courses but ensuring that is an optional enhancement to the experience rather than compulsory, so as not to exclude any participants.

- Enabling social interaction

One of the key findings from our Strengthening Research and Knowledge Systems (SRKS) programme was that social interaction is very important for the success of online learning.

Much of this interaction comes from the facilitation of the courses. With high numbers of participants – in the thousands for our research writing massive open online courses (MOOCs) – came the need to increase the number of  facilitators. We have used the Community of Inquiry Model by Garrison to guide us in the development of the MOOCs, and have developed a guest facilitator model where people from partner countries support online discussion. This strong facilitator presence differentiates our MOOCs from others, providing greater scope for social interaction and, we believe, contributing to our significantly higher completion rates than typical.

facilitators. We have used the Community of Inquiry Model by Garrison to guide us in the development of the MOOCs, and have developed a guest facilitator model where people from partner countries support online discussion. This strong facilitator presence differentiates our MOOCs from others, providing greater scope for social interaction and, we believe, contributing to our significantly higher completion rates than typical.

- Facilitating reuse, customization and local ownership

During the course of our SRKS programme, which ran from 2013 to 2018, we worked with partners to help them embed AuthorAID research writing training within their researcher training programmes. Initially we focused on face-to-face training approaches, but access to digital technologies has evolved rapidly in many countries (along with an appetite for using Moodle), and we soon saw demand from partners for online components.

There are particular advantages of integrating online components in training programmes where researchers are distributed across several sites or out in the field and some partners – such as the Tanzanian Fisheries Research Institute (TAFIRI) – have embedded online learning based on our AuthorAID courses across all of their sites.

With this demand in mind, our course material is developed and structured into packages that can be easily downloaded, customized and embedded into partners’ own digital platforms. This makes it easy for partners to reuse, repurpose and add their own resources that are context specific.

- Co-planning for sustainability

All of INASP’s capacity development approaches are underpinned by the principles of sustainability and local ownership, making sure that we support lasting change and that capacity development can continue once INASP is no longer involved. We develop plans for sustainability together with our partners in the early stages of each project. Rigorous scoping activity allows us to understand what is possible in each context and tailor our support to local needs. Our courses can persist in various formats and ways of delivery, depending on what will maximize their use and engagement.

We have recently developed a checklist tool with criteria for local embedding and will use it to co-develop embedding plans that build on what exists already, maximizing our time, effort and resources to support the major areas of need. We are also working on converting previously developed taught-course materials into self-study online tutorials that anyone can use at any time.

***

We have learned that all five areas above are essential contributors to the success of online and blended learning interventions and they all must be given equal attention in the conceptualization and design processes. We believe that this is why participants tell us about good learner experiences and useful and transferable learning from INASP’s online and blended courses.

For more information, contact jwild@inasp.info.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post