Evidence reading: Innovation in organizational change

Innovation in development has been the ‘buzz’ word of the last couple of years. We all talk about it but do we really know what conditions trigger innovative solutions to complex problems?

As we begin our organizational diagnostic of knowledge use in Peruvian public administration, I have been revisiting material on organizational change, innovation and public reform. I came across a wonderful article – Creating Breakout Innovation by Joanna Levitt Cea & Jess Rimington from the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

This article summarises five practices that make a difference for creating innovative outcomes: Sharing power, prioritise relationships, leverage heterogeneity, legitimise all ways of knowing, prototype early and often. While this list may sound familiar, how ready are we (individuals and organizations) to implement these practices?

-

Sharing power

When I think of sharing power I tend to imagine handing over decision-making or soliciting people’s opinions and views before making decisions. Consulting and taking a participatory approach means sharing power, right? Levitt Cea & Rimmington take this a step further – to truly share power, they say, people must be considered not just as inquiry subjects, but also as engaged researchers, analysts, and decision makers. Organizations that open up their internal processes – involving clients in idea generation, for example – are successfully creating spaces for decision-making.

For me, a power sharing environment is a free (sometimes messy!) space where everyone has an equal say. But as the authors rightly state, power sharing needs design and structure. They give the example of Incourage, a community foundation in Wisconsin Rapids (USA) that enabled citizens to actively shape and determine their organizational mission. Other examples of genuine power sharing, include local government’s participatory budget processes, where citizens decide how to allocate public resources; and self-managing organisations, like Buurtzorg, a health care company in The Netherlands where front-line workers (in this case nurses) are given decision making power. At Buurtzog, there are virtually no hierarchies, no management team, and the CEO can’t make decisions for the teams.

In a recent blog post I explained how we are applying this idea of ‘sharing power’ in our organizational diagnostic of a Peruvian public agency. Here, participants become researchers of themselves – authors of their own assessment, deciding which aspects are important to highlight and take forward.

-

Prioritizing relationships.

Reading this article was an opportunity to self-assess how I manage relationships at work. Levitt Cea & Rimmington state that relationships are built on ‘fair deals’ or what they call commitment. People want to be involved in projects where decision-making is shared, where they identify with its values and there’s room for participation and creativity. Producing co-commitment takes projects to a much higher level, because people care and will go the extra miles to progress together.

This was one of the key considerations of our call for public agencies wishing to improve the use of knowledge in public decision-making. In the current international development system, per diems and allowances are often a challenge to navigate. These payments sometimes hinder people’s commitment to a change process. We decided not to offer payment as our goal was to work with a motivated group who wanted to co-innovate, co-create and co-learn. We were nervous of how this could affect response, but in fact, we received more than 20 proposals from teams that also want to work in this way.

-

Leverage Heterogeneity

At INASP, we are very conscious of the value of heterogeneity and diverse perspectives. Levitt Cea & Rimmington highlight how heterogeneous groups can drive innovation, but make note of the pitfalls of ‘empty heterogeneity’ – when heterogeneity exists at a superficial level. A good example of leveraging heterogeneity is Eneo, an electric company in Cameroon, who combined teams and levels of hierarchy to solve pressing issues faced by clients. The solutions identified had almost no financial cost. Of course, skilled facilitation is crucial to this process.

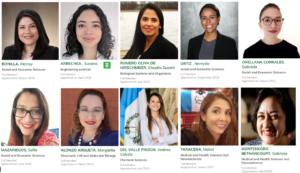

We are planning to make the most of heterogeneity in one of the workshops with the Peruvian agency which invites external stakeholders, and members of the knowledge production sector. This means not only research institutes and university research centres but also NGOs, CSO, unions and relevant actors whose views could be valuable for solving policy problems.

-

Legitimize All Ways of Knowing

This one is an interesting point for somebody who, like me, is working on evidence informed policy. Increasingly within EIPM, we are using the world ‘knowledge’ rather than ‘evidence’ as the latter implies only verifiable fact. Levitt Cea & Rimmington highlight that all types of knowledge are important in innovation projects. We are all aware of how challenging this is, particularly when ‘expert’ advise tends to take the lead.

While other knowledge such as intuition and unconscious insights are increasingly taking a role in the social sector (the recognition of meditation, for example, to access deeper knowledge) it is still in the fringes. Levitt Cea & Rimmington mention Theory U, inspired by a study that Scharmer and colleagues conducted on the habits of highly creative people. All reported having an intimate relationship with a deeper source of knowing—their moments of greatest insight happened when they found themselves feeling connected to this source.

I think it is important to emphasize the word ‘legitimize’. It is not about shifting to entirely alternative (rational) ways of knowing, but to recognize that all knowing is important – from scientific to intuitive knowledge.

This a difficult one for us to implement in the Peruvian case. We are dealing with a government agency which by definition is bureaucratic and hierarchical, with traditional way of working. The people involved are researchers and scientists, sometimes more wary of giving room to alternative ways of knowing. However, we do want to explore this crucial element and we will be including experiential techniques that allow people to access their deeper knowledge – such as ‘transformational scenario planning’.

-

Prototype Early and Often

We have heard this one several times – from design thinking, adaptive management and innovation literature. However it is not easy to do well. As the article suggests, prototyping too much and too often can create fatigue.

In our sector it’s also about finding the funds that will allow prototyping – this is a challenge when feasibility studies and political economy analysis sometimes take so long that little time is left for testing new approaches. Prototyping requires a change of mindset. It requires investing in action early on to see what works rather than waiting for lengthy studies to say what is (or isn’t) feasible. Again, the process of prototyping requires structure, for it to be successful.

We are looking forward to taking a prototype approach in our Peruvian case. After diagnosis, and prioritisation of issues, the planning phase will include the co-creation of a few prototype ideas that the agency can put into action, without investing too much money or time. The projects that get traction can be then scaled up if the time is right.

Creating Breakout Innovation has led to much self-reflection on the work we are starting in Peru. Maybe it will also help you assess some of your own activities or inspire practices to develop breakout innovations!

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post