In Uganda, education students are bringing new ideas about learning into local schools

18 months on, the change seeded by the TESCEA programme – a partnership to transform the relevance and quality of learning and improve the prospects for young people in East Africa – continues to grow. We recently talked to Albert from Uganda Martyrs University, a TESCEA partner university. He tells us that the pedagogical approach fostered by TESCEA is actively being used by education students in Ugandan schools, how university staff has become more gender responsive, and that former TESCEA team members continue to push for pedagogical and structural changes that foster the employability of their students.

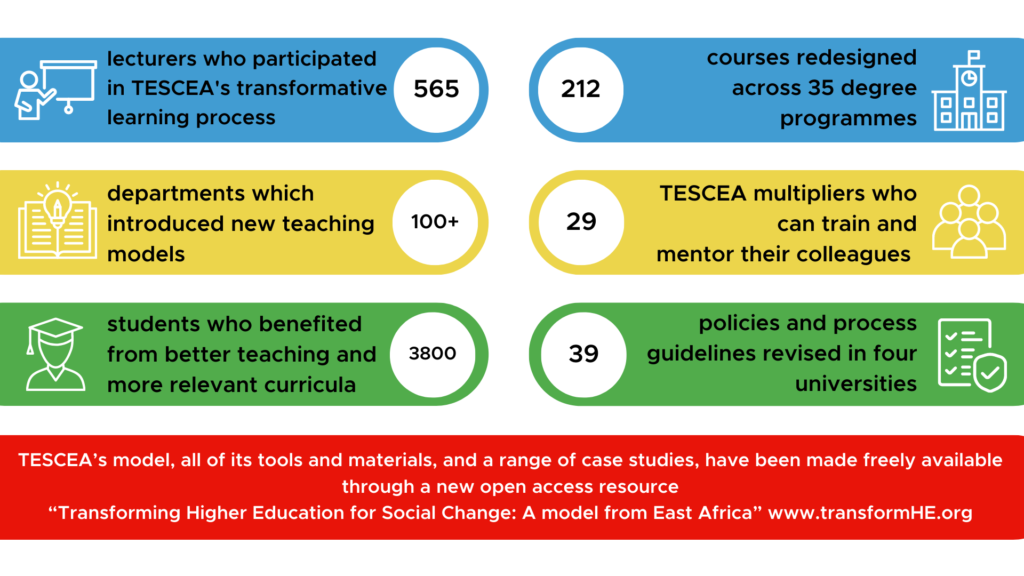

From 2018-2021, the Transforming Employability for Social Change in East Africa (TESCEA) partnership developed a scalable pedagogical model to help universities produce graduates with the critical thinking and problem-solving skills they need to solve real-world problems.

Here are some of the partnership’s key achievements:

From our evaluation we know that TESCEA facilitated tangible changes in teaching practices, student learning and institutional processes, systems, and cultures. 94% of lecturers believed that the new approaches were more effective and enabled them to develop more relevant courses and more learner-centred teaching and assessment. The use of critical thinking and problem-solving techniques increased by 43% while the use of active learning strategies by 37%. 87% of students at the four TESCEA partner universities rated their learning experience as positive. 94% of senior university managers felt the changes were very important to their institution. Read more about TESCEA’s impact here.

From our evaluation we know that TESCEA facilitated tangible changes in teaching practices, student learning and institutional processes, systems, and cultures. 94% of lecturers believed that the new approaches were more effective and enabled them to develop more relevant courses and more learner-centred teaching and assessment. The use of critical thinking and problem-solving techniques increased by 43% while the use of active learning strategies by 37%. 87% of students at the four TESCEA partner universities rated their learning experience as positive. 94% of senior university managers felt the changes were very important to their institution. Read more about TESCEA’s impact here.

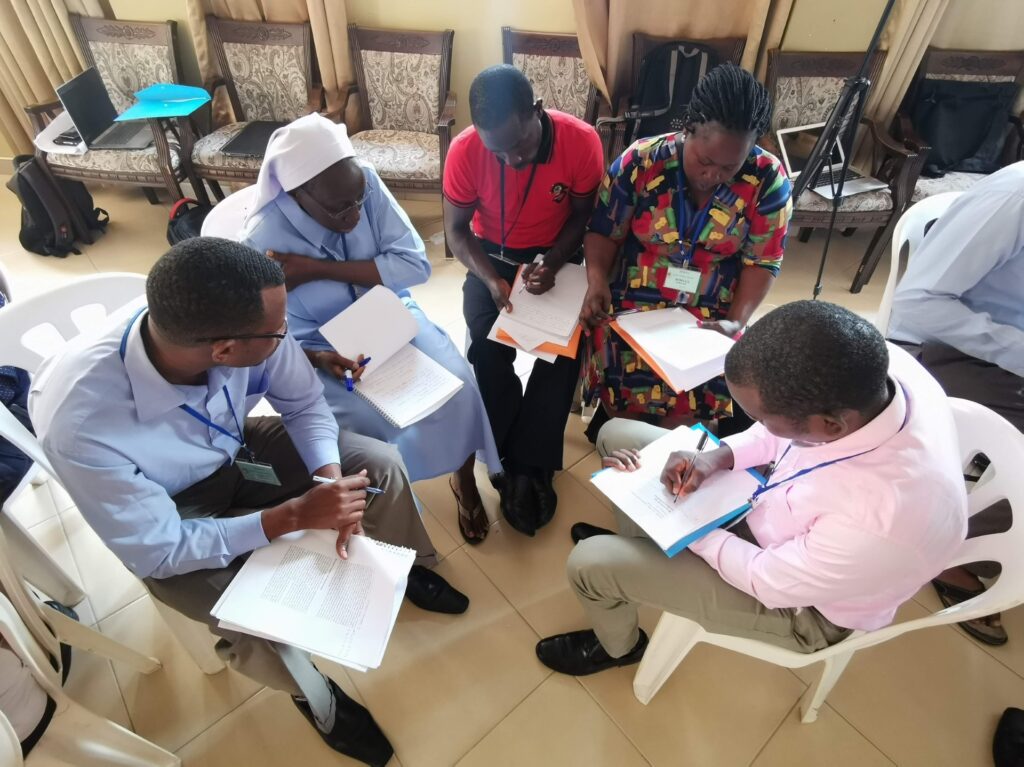

We are now working to scale TESCEA’s approaches to further universities in East Africa and beyond. In the meantime, we caught up with lecturers from the four TESCEA universities to hear how they’ve been doing since the first phase of TESCEA ended, and to learn more about what impact the project left behind.

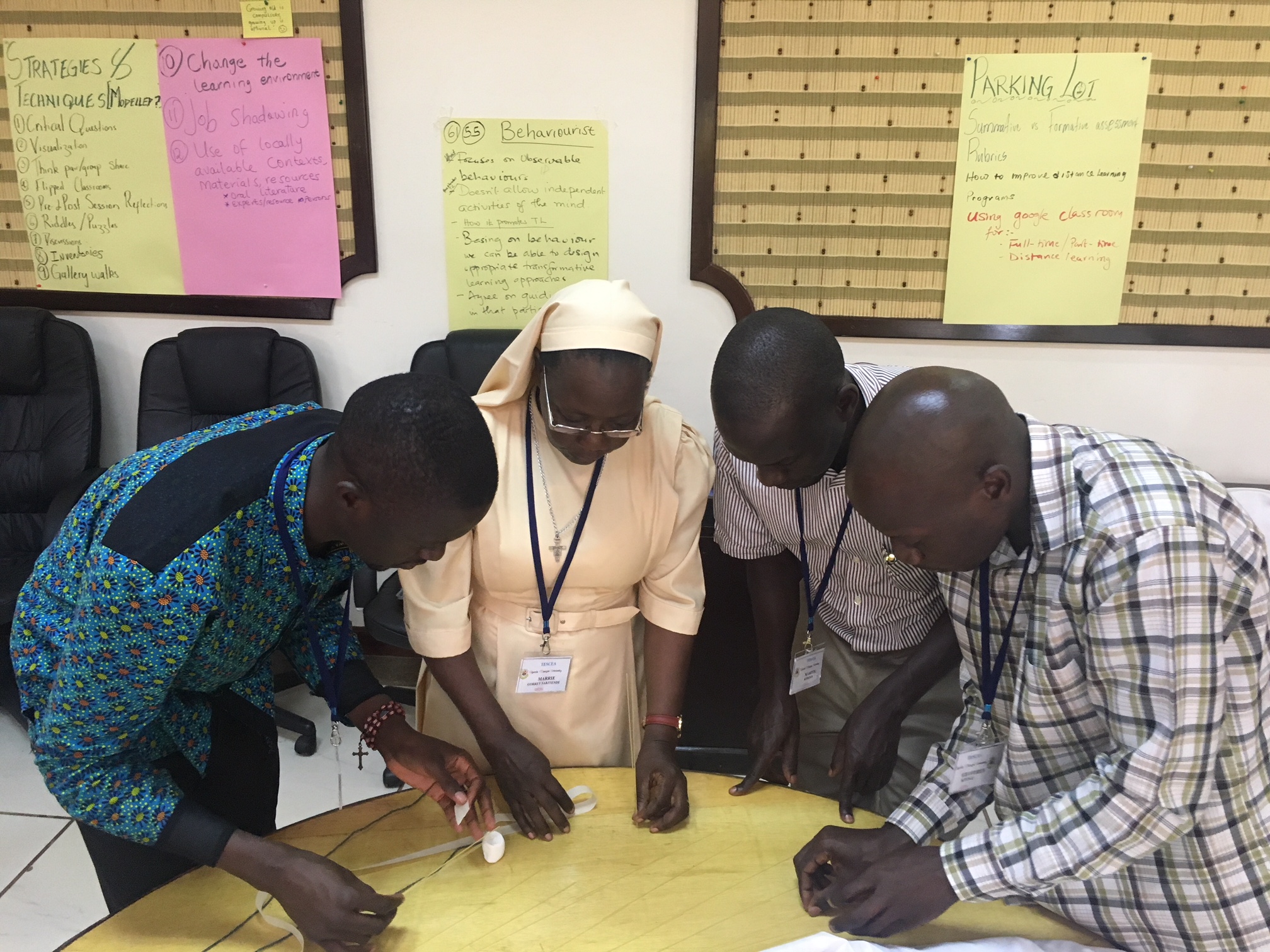

This week, we checked in with Albert Luswata from Uganda Martyrs University (UMU), which and re-designed 54 courses during phase one of TESCEA, building an impressive team of multipliers [as a result of a train-the-trainers effort].

Albert has been an engaged TESCEA team member, gender champion, and overall ambassador for the project from day one. He helped facilitate multiple workshops at his university and has been advocating for policy changes, especially around gender issues, at UMU. Read below what he had to say.

Albert, what has been happening at UMU since the first phase of TESCEA ended?

Albert: Probably the most obvious is that we continued the application of the new pedagogical approaches that we learned about. We have not done any formal survey, but in an informal way, through interactions with both students and staff, we know that the work is continuing – especially in the way many people teach. Many of those who underwent TESCEA training are applying the new pedagogy [TESCEA approach]. Although there are probably still some colleagues who, for convenience, returned to their old ways, especially after the pandemic passed and things went back to normal, but not totally. There are certain things that you really can’t go back to after learning the TESCEA way [including the pedagogical approaches – read more here]

Can you give us any examples from specific departments or programmes?

When it comes to the students, we came to realize that our education students who became teachers, or those who went for internships, apply these TESCEA approaches themselves and many of them have become very marketable in the schools where they interned. Many of them have been retained, and they’re doing well, based on what we know from the staff monitoring them. So, the education department is one of the faculties where you immediately see the impact of the pedagogical changes and some other TESCEA activities.

It’s clear that teaching practices have changed then. But we know institutions only change when some of the policies and processes change – I know you devoted a lot of attention to that.

There are things for instance, that needed restructuring within the university systems. We had [revised] some policies to integrate the TESCEA approach [and] some were enacted. For instance, we have someone who is the focal person to ensure that there is ongoing training of staff and was put under the Directorate of Postgraduate Studies, and we’re trying to find a way to work with him. Of course, there were challenges with funding and all the other activities that we had to do, but at least the university put this position into the structure.

What’s been harder to sustain?

It’s been hard to sustain the level of interactions with the Joint Advisory Group [JAG], and the student clubs have not gone on as we had envisioned – there have been some post-pandemic funding issues due to low student numbers. But we hope to be able to revive those as well as the JAG. The university Vice Chancellor and the DVC both mention TESCEA frequently and call upon the TESCEA team of multipliers to engage in various activities.

Thank you, Albert, that’s really interesting – especially that the education students have already become more employable and are even multiplying the approach in other schools – which was the goal of TESCEA journey.

Have you seen any impact regarding gender-responsive pedagogy?

Albert: Yes, I think there is evidence that shows that people are more gender responsive. I think it’s changed compared to how it used to be. Like I said, we have not done a formal follow-up on this. But our staff discussions and in-class experience show there is more sensitivity to inequalities, which was not the case before. So, it is ongoing. And I think when you hear colleagues talk, they’re very gender sensitive, and they promote that equity in the classroom setting. Though, new challenges come in, for instance, when we have to teach online. There are a number of things we probably did not think about before. But in the physical classrooms, a lot has been done. Certain things don’t depend on the individual lecturer though, like the structure of the classroom. Because the entire environment is very key to influencing what goes on in the classroom.

We have also been continuing to remind colleagues and management of the importance of the continuation of gender responsiveness, also to balance genders in the positions of higher responsibility, because this impacts the decisions that are made about the university. I would say some things could be even better. It’s a continuum, it is something that we need to continuously remind ourselves of, and, you know, it doesn’t come immediately – due to the cultural issues, the structural issues, and so many things, but I think the [TESCEA gender] champions are continuously reminding everyone to ensure that we don’t lose track on these issues.

Absolutely, change doesn’t happen overnight, but it is good to hear that the gender champions keep pushing for it. Have the other multipliers that were trained continued to support university staff and new lecturers coming in?

Albert: Yes, the team is actually still alive. We lost some colleagues who have left the university. But the team is still there. We have had a few meetings, there were some faculties that had requested us to train the staff that missed out during the project. We had also got some appeals from other universities that wanted us to go train them. Although we didn’t end up actively going there, it helped us to see what we need to do next. We have also oriented new students at the beginning of the academic year. A number of us have participated in a digital pedagogy skills training by a visiting scholar from the US. So, the team is there, we try to keep ourselves updated and help others both individually, but also as a team in the form of trainings.

What would it take for UMU to continue the TESCEA journey?

Albert: In my view, the process of structuring the project within the university through policies and practices is very key. We definitely had a big buy-in, although we had challenges when the project ended. The post-pandemic situation was a key issue. We had two student intakes in which the university had very few students and financially, there were many challenges and the university has had to prioritize other things. We are beginning to stabilize countrywide, but the challenge was very big. So, you will understand that funding had to go towards other top priorities for the university.

Another challenge we have is that TESCEA team members are also fully engaged in other activities. It becomes a bit challenging to manage it all. After the project ended, the enthusiasm that comes with a project, of course, goes down. I think we need to engage the university structures more and remind ourselves of certain things, because there were so many beautiful things in TESCEA.

It would also be good to do a follow up on what transpired in the first phase, going to see where our students went, see how are they doing differently than the ones that were not affected by TESCEA.

For me, the engagement with members from the community and from the industry was very important, but we have lost a bit of touch of that. I think that’s something that going forward we need to strive to achieve.

If you had the opportunity to directly address funders and influence national and regional bodies, about TESCEA, what would you tell them?

Albert: Oh, I would say that TESCEA provides what has been missing in terms of linking what we do in education institutions, especially higher education institutions, with what is needed in society. It provides that platform to link the higher education institutions with industry and with the government. I think it would solve a number of questions that society has, especially about skills that the society needs in the 21st century.

I think it’s very, very important to have a project like this one. It’s very timely. What we did was very nice, but the period was too short to really see this seed blossom. Funding needs to target a longer period so that you don’t begin something good and then stop. Change needs time and planning.

TESCEA’s model, tools, materials and publications are all freely available via https://www.transformhe.org/.

We are currently working with strategic and funding partners to develop the second phase of TESCEA. Get in touch if you share our ambitions for transforming education, employability and young people’s futures: contact Jon Harle.

The partnership for the first stage included four universities (Gulu University and Uganda Martyrs University in Uganda, and the University of Dodoma and Mzumbe University in Tanzania), who worked with AFELT and Ashoka as support partners in Kenya and with INASP as support and lead partner in the UK.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post