How do you build a ‘system view’ of a country – and then what do you do next?

In the last year or so we’ve been grappling at INASP with what it means to take a systems approach to capacity building (and we’re not the only ones thinking about this, as ITAD’s framework suggests).

As we blogged last year, we have begun by trying to develop a more detailed ‘systems’ view of some of the countries in which we work. It’s an exploratory approach – and these are by no means detailed, in-depth pieces of analysis. But they do give us a much richer understanding of some of the key enablers and obstacles to our work. And they show that light-but-valuable analysis of this type is within the scope of even a small NGO like INASP (we currently have around 30 members of staff, working in over 20 countries).

Step one: a quick sketch

We’ve taken a two-stage approach. Firstly we’ve quickly mapped the research and knowledge system as we know it. Here we build on background country profiles we commissioned a couple of years ago, but also the collective knowledge of the team – which also enables us to draw together knowledge from different parts of our work and the team’s knowledge.

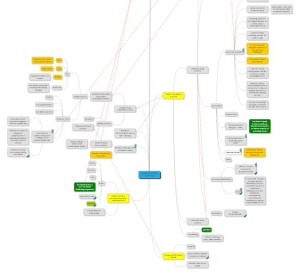

We’ve been using some free mindmap software to do this, which  enables us to plot some of the key organizations in clusters, related to the different aspects of our work (access to research, research communication, evidence-informed policy), and to the key policy or decision-making groups (national research councils or similar). Of course these are by no means comprehensive maps – but they give us a way to make sense of what we already know, and to fill in some of the gaps through basic desk research.

enables us to plot some of the key organizations in clusters, related to the different aspects of our work (access to research, research communication, evidence-informed policy), and to the key policy or decision-making groups (national research councils or similar). Of course these are by no means comprehensive maps – but they give us a way to make sense of what we already know, and to fill in some of the gaps through basic desk research.

Step two: get on a plane

Step two involves a visit to the country. We have taken two week-long trips to Nepal and Tanzania as part of this strand of work so for, with a team of three or four senior staff – as well as a number of lighter country visits, which haven’t had the full ‘mapping’ beforehand, and have involved fewer people, but have still enabled us to go beyond our existing partners.

Although short, our visits to Nepal and Tanzania were fairly intensive. During a week in Tanzania in January we met representatives from 16 different organizations, having rich conversations with around 50 individuals involved in producing and using research and knowledge. These have included current partners, government agencies responsible for research and higher-education policy (COSTECH); regulation and funding bodies; universities (including various departments from research to continuing education to libraries); research institutes (such as REPOA and ESRF); and NGOs with an interest in the local research and knowledge system (a visit to Twaweza left me particularly excited).

A visit to Nepal last April was similar in scope. Amongst out visits were Tribhuvan, Kathmandu and Pokhara universities, the Social Science Baha, the University Grants Commission, the regional Himalayan research institute, ICIMOD. We met the editor of the Nepali Times, and a team at the Nepal Administrative Staff College (NASC).

Step 3: get back and try and figure out what we learnt

Aside from a stack of new business cards, a clutch of reports, and endless meeting notes what did we come back with? Both Nepal and Tanzania are countries where INASP has worked and provided support for a decade or so. Our staff – and the staff of partner institutions – has changed considerably in that time. What’s more, while we have had trips to each country several times over the years they have more typically been focused on a particular workshop or event.

We returned on both occasions with a much better understanding of what was happening in the country, and where we fitted into that. It helped us understand some of the day-to-day dynamics, drivers and politics of work in this area. It enabled us to strengthen relationships with existing partners (nothing beats sitting down together for an hour or two) and it helped us to see where our aims overlapped, and in some cases where they were slightly different.

We updated our ‘sense’ of how the research system was doing too, and heard about some new initiatives and ideas.

And it’s often the chance conversations, and the energy (or lack of) in someone’s voice that gives you an insight into how things are going, and the opportunities or obstacles to progress.

In Nepal we were particularly struck by the politics of the system – and that caused us to re-assess the extent to which we could support or facilitate change. We made the effort too to learn about the particular challenges that female researchers face in Tanzania– over an informal dinner hosted by two female members of staff. Women’s voices and perspectives can be easily lost in relatively male-dominated environments.

We learnt some things of value to our wider work in both cases too. We learnt where we need to get better at communicating with partners to ensure we really do have a shared understanding and what needs to be in place for our work to be of value – something we think about in terms of readiness, or minimum conditions.

What have we done as a result?

In Nepal we realised that, for the handover of the Nepal Journals Online (a service that INASP established, but which Tribhuvan University is taking on) to be successful, we needed to create wider interest in the platform, and make sure it was better known. This led us to increase our communications support to the project.

In Tanzania we learnt that (not surprisingly) there are many organizations working in this space, and that, as a result, some institutions are simply overwhelmed with support. It’s still needed – but at a pace where it can be absorbed and the partnerships managed. This has helped us think through how to identify the most appropriate partners for the relatively modest support we can provide. Perhaps that means smaller institutions, or newer institutions without so many existing international links. We also learnt (again, unsurprisingly) that if we’re going to be successful embedding our researcher training (in an institutional training programme or curriculum) – a key plank of our sustainability strategy – then we need to spend more time with the partners early on to understand the institutional environment.

But perhaps the experience that sticks in my mind is a brief ride in a bajaji (a Dar es Salaam tuk tuk). Our driver wanted to know what we did and then offered his own analysis of Tanzania’s problems since independence. But what sticks in my mind most was the challenge he gave us: could we explain our work, why we’d come to Tanzania, and how this had anything to do with addressing some of the daily struggles of life in Dar es Salaam? He didn’t need much convincing of the importancet of education and knowledge.

Hi Jon, thanks for a very insightful and thought-provoking blog.

I think that – resources permitting – it could be really interesting to apply your systems mapping approach to different scales of analysis, drilling further down than the country level. For example, the interdependencies and feedback loops operating at the kind of macro, country level are clearly so different to the dynamics you see as you zoom in up close. So I think it could be a really interesting exercise in your Tanzania project to map the smaller institutions you may end up concentrating on as their own systems, and think about interconnections between the different departments and infrastructures (e.g. libraries, research management offices, ICTs etc). This might allow you to consider the many different “entry points” for embedding INASP’s researcher training within programme structures, and involving the local partners in this preliminary analysis stage will help contribute to the project sustainability.

(Incidentally, one quite interesting potential model for this kind of micro level systems mapping appears in this paper by Ben Ramalingam (http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9159.pdf), looking at trade dynamics at a single border crossing point between Nigeria and Niger. It’s obviously quite a different context, but all the abstract ideas around identifying interdependencies and feedback loops which then allow you to identify where and when an intervention can have the biggest effects might still be worth considering).

And another quick question – when you do these country mappings, do you include INASP itself as an actor within the system? If not then I wonder whether incorporating INASP into these maps (at least as a temporary element within the country system…) could help better identify the multitude of interlocking relationships and pathways crucial to the success of an intervention, and help you to envisage possible obstacles and consider solutions.