Gender-responsive pedagogy in higher education: How we are approaching it in TESCEA

Mai Skovgaard shares how asking important questions and running daily sessions on gender within university course redesign workshops helps participants reflect on how gender responsive they are in their teaching as well as how they can make changes to become more responsive.

What are the gender inequalities that exist in your country? How do these inequalities affect your students?

Do your course materials reproduce these social inequalities? What can you do differently to challenge and transform gender inequalities?

University teaching needs to include and enable opportunities for all students. An important component of this is ensuring that teaching and learning processes pay attention to the specific learning needs of female students and male students.

The Transforming Employability for Social Change in East Africa (TESCEA) partnership is working with teaching staff on selected courses within four universities in Tanzania and Uganda so that the courses can better equip students with the critical thinking and problem skills they need after they graduate. Within this project, a key aspect is piloting a new approach to gender-responsive pedagogy in higher education.

As FAWE’s Teacher’s Handbook for Gender Responsive Pedagogy, which we have drawn on in this work, says:

“Gender-responsive pedagogy calls for teachers to take an all-encompassing gender approach in the processes of lesson planning, teaching and learning, classroom management and performance evaluation.”

However, to date there has been little work on gender responsive pedagogy in higher education.

Earlier this year, our Project Steering Group looked at how to better integrate gender, including gender responsive pedagogy, into TESCEA in a more systematic way and agreed on the following definition of gender responsive pedagogy across the partnership:

“Gender responsive pedagogy in TESCEA means that…

-

The learning needs of male and female learners are addressed in teaching and learning processes (inside and outside of the classroom)

-

Teaching staff are gender-responsive in their planning and facilitation of courses, and continuously reflecting and adapting.”

"We normally do it unknowingly, but since we know now we will do more to make sure that gender is well represented" – participant at @udomofficial's course redesign session #tescea #spheir #genderresponsive @INASPinfo

— Mai Hoff Skovgaard (@maiskovgaard) September 13, 2019

In practice this means that, within our course redesign workshops we work with faculty to think through gender as it relates to their:

- Teaching and learning methodologies and activities

- Teaching and learning materials

- Classroom interactions

- Classroom management and set up

- Language

- Learning spaces and campus life

An important area of focus has also been on students as future gender responsive professionals and the link this creates to industry.

Bringing gender thinking into course redesign

We have worked on the methodology for and facilitation of gender responsive pedagogy with several stakeholders. These include our project partner AFELT and an external gender consultant. They also include so-called gender multipliers from each of our partner universities. The multipliers were trained in a Training of Trainers workshop earlier this year to take on facilitation roles. (Read more on the multiplier approach within the TESCEA partnership here.)

Over the course of the course redesign sessions we have helped participants to build up a more thorough understanding of gender and gender responsive pedagogy by looking at these concepts from different perspectives:

- Gender as representation – for example, the gender balance reflected in university promotional materials

- Gender as equality/equity – the gap between the aspiration and the reality

- Gender as stereotypes and (conscious/unconscious) bias – what stereotypes need challenging about male/female learners

- Gender as internalized bias – how gender relates to grades and assessment

- Gender as interaction and space – reflecting on classroom settings, for example where students sit and who speaks more

- Gender as power/empowerment – ensuring that power and knowledge don’t just flow one way

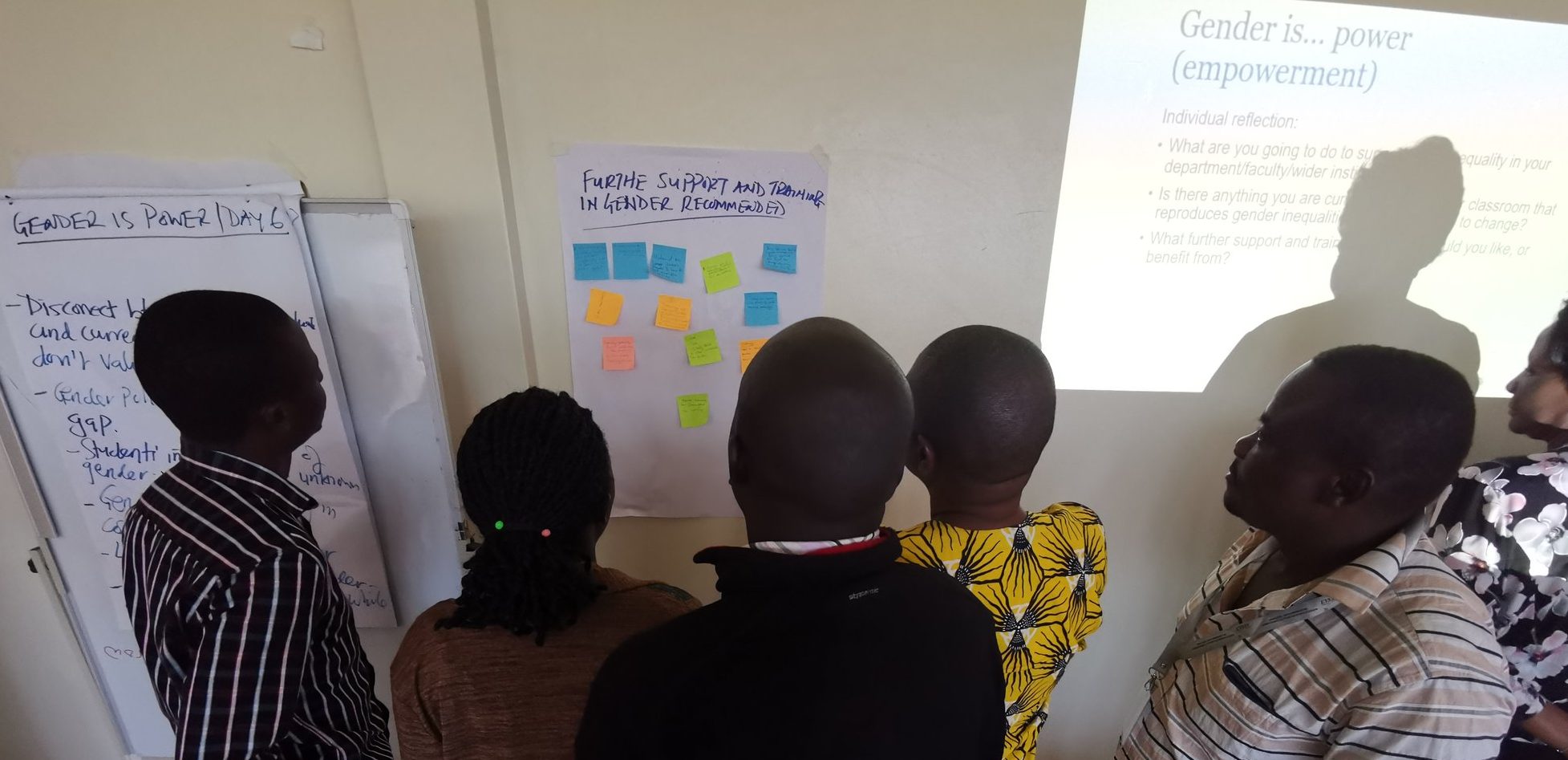

What are you going to do to support gender equality in your department? What further support and training in gender would you benefit from? @TesceaG is wrapping up the last gender session in this week's #courseredesign workshop. @AFELT2 @INASPinfo @dfmonk #TESCEA #spheir pic.twitter.com/enGqdmH1tM

— Tabitha (@TabithaBuchner) August 29, 2019

Challenges and learning

There are some challenges. There is not always an immediate understanding of the need for being gender responsive. We address this by doing gender sensitization as part of TESCEA workshops. This enables us to explore the gender gap within a country more broadly and within higher education in the country in particular.

We often find that there are more men than women in our course redesign workshops. While there is an ambition for equal representation, this can be limited by the balance within a university as a whole and also by which people are teaching in the specific programmes that are being redesigned.

There is also a challenge because gender-responsive pedagogy is new to participants. We can help participants to start thinking about it during the sessions, but it will take longer to see how these approaches affect what happens in the classroom.

Although it is still quite early days with this work, we have some broad observations about how gender responsive pedagogy within higher education should be approached:

- First, it is important to be mindful of context. This is what we do with gender sensitization, starting with the country and what the gender context looks like within the country.

- Following on from this and situated within the national context, there is a need to look specifically at gender in higher education. We need for lecturers to think about teaching and learning processes from a gender perspective and also to think about what they are preparing students for beyond university.

The third dimension of this is engagement with industry. As lecturers are preparing their students to become future professionals it is important that the outside world is brought into and reflected in the classroom.

INASP and the TESCEA partnership are deeply committed to learning and adapting. We would welcome thoughts and ideas on gender-responsive pedagogy in higher education from others working in this space.

Do you have any experience with gender responsive pedagogy in Higher Education and building the capacity of lecturers in this area? How have you approached this topic?

***

Transforming Employability for Social Change in East Africa (TESCEA) is helping young people in Tanzania and Uganda to use their skills and ideas to tackle social and economic problems. With partners in Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya, TESCEA supports universities, industries, communities and government to work together to create an improved learning experience for students – both women and men. This improved learning experience fosters the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills, and allows for practical learning beyond the classroom that improves a graduate’s employability.

The TESCEA partnership is led by INASP (UK), working with Mzumbe University (Tanzania), University of Dodoma (Tanzania), Gulu University (Uganda), Uganda Martyrs University (Uganda), Association for Faculty Enrichment in Learning and Teaching (Kenya), LIWA Programme Trust (Kenya) and Ashoka East Africa (Kenya).

TESCEA is funded by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) as part of DFID’s SPHEIR (Strategic Partnerships for Higher Education Innovation and Reform) programme to support higher education transformation in focus countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

To learn more about TESCEA, click here. To learn more about INASP’s Gender Responsive Pedagogy in Higher Education Framework, click here.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post

With the understanding that gender-sensitive teaching aims at equally supporting the learning of male and female students, this disparity calls for the promotion and adoption of gender responsiveness teaching practices in higher learning institutions (HLIs) to correct gender bias in the learning process. The argument here is that the teaching and learning environment in higher learning institutions is not only gender-imbalanced but also it is not well known on whether instructors are aware of gender sensitive teaching techniques, and to what extent do they mainstream gender sensitive teaching practices in their daily teaching practises.