Enabling social change from changes in higher education

Last week the leadership team of the Transforming Employability for Social Change in East Africa (TESCEA) partnership met to reflect on our first two years and look ahead to ensuring lasting impact. Jon Harle shares some of the reflections on the implications of TESCEA for wider society.

Nestling at the heart of our partnership’s name are two important words – social change.

Since we embarked on the Transforming Employability for Social Change in East Africa (TESCEA) work together, the idea that universities and their graduates have roles to play in benefiting wider society has underpinned many of our conversations.

Students – and later graduates – who can think critically and apply their skills to solve problems have a greater potential to contribute, whether through business or public sector roles, or as citizens and members of their communities.

To have an opportunity to develop those skills, we have been working to re-design courses and rethink pedagogies, but we’re also thinking about opportunities for practical learning beyond the classroom. This is one way that students can begin to connect what they study to the needs of communities, or wider society.

But despite this shared concern for social impact, we realised we’d been relatively silent on how this was happening, and what we hoped to see. During our annual partnership planning meeting last week in Uganda, we sat down together to think about this, and asked ourselves the question again: how can or does university teaching and learning contribute to social change in East Africa?

Changing organizations

We spent quite a bit of time thinking about institutional or organizational change. At first this felt like we might be missing the bigger question – of impact beyond the university – but it became clear as we talked that the first steps towards wider social change have to be change at the institutional level. We need to shift the norms, policies and practices on campus, for both staff and students, in order to provide the conditions for social change to emerge.

As colleagues noted, lecturers are already beginning to see their roles differently. They are starting to understand that they need to become facilitators of learning, not just transmitters of knowledge. Through the course re-design process, they are beginning to connect their curricula more strongly to real-life experiences, and to divide learning time between the classroom and community.

As a result, students are also becoming more active participants in the learning process and are sometimes even taking facilitative roles alongside their lecturers in the classroom.

In some cases, TESCEA is building on existing foundations in each institution, although bringing a new focus to these issues. It is also encouraging those foundations to expand and grow, and to orient more strongly towards the needs of local communities, or of entrepreneurial modes. In other cases, entirely new initiatives have been developed.

Influencing change beyond the university

We are also recognizing that the boundaries between university and society are porous. Changes that happen within the university also have the potential to influence actors beyond the campus. As staff and students move between campus and their off-campus lives, their values, ideas and choices inform their interactions beyond as well as within the institution.

Communities are becoming more involved in university teaching and learning, through engagement in the Joint Advisory Groups (local groups set up by each university partner to engage with wider stakeholders in businesses and their communities), or as guest speakers, or hosts of projects and placements. As this happens, communities are also beginning to shift the way that academics and students think, and the way that universities understand their current and future roles.

Students are engaging with their communities through placements and projects that the university initiates, as part of the formal learning programme, but also informally through initiatives that students have been inspired to create. At the University of Dodoma in Tanzania, a series of student clubs have been established, one running its own conference to encourage students to think about preparing for their lives as graduates, another focusing on entrepreneurship. Uganda Martyrs University is adopting the social entrepreneurship model for student clubs, so students demonstrate the social impact of what they are doing.

In some cases, attitudes are starting to shift. Agriculture students at Gulu University have been supporting a pig farmer to refine feeding, improve management of hygiene and vaccinations, while local hospitals have recognized the value of Gulu’s medical graduates, who are more aware of the needs of rural communities.

At Uganda Martyrs’ University, education students work with a school for deaf and blind students, which is both a training opportunity for students, and a chance to share skills, while in another faculty students have helped to organize microfinance initiatives and are doing research into the impact.

Lecturers in Dodoma noted that their students weren’t always willing to engage in this way – but are now much keener to be part of a collaborative problem-solving process when they work with the rural community on field placements.

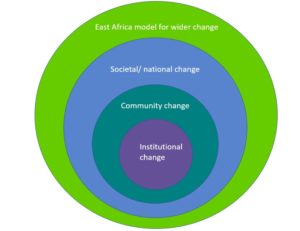

Visualizing social change in TESCEA

As we talked and shared ideas, we began to see that the project’s contribution to social change could be expressed best as a series of concentric circles, from the institution in the middle, moving out to community and to wider society, and potentially and ultimately moving from national to regional level. As well as a spatial dimension, these rings have a temporal aspect – as change proceeds over different time frames.

from the institution in the middle, moving out to community and to wider society, and potentially and ultimately moving from national to regional level. As well as a spatial dimension, these rings have a temporal aspect – as change proceeds over different time frames.

We also identified some different types or categories of change, that we might expect to see, or want to be conscious of:

- The greater inclusion of disadvantaged groups in learning on campus, and engagement through off-campus learning

- The creation of a culture within the university (and ultimately beyond) that values and advances critical thinking and problem solving

- Impacts on market dynamics and value chains through engagement in business and entrepreneurship

- Impacts on public policy, or on the norms of business and industry, including encouraging business to think more about social benefit

There is more to do, as we enter our third year of the project – and our fourth year working together as a partnership – to think about these questions, and to forge the connections between teaching, learning and wider society. But we have a shared ambition, and a clearer sense, collectively, about some of those pathways.

***

Transforming Employability for Social Change in East Africa (TESCEA) is helping young people in Tanzania and Uganda to use their skills and ideas to tackle social and economic problems. With partners in Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya, TESCEA supports universities, industries, communities and government to work together to create an improved learning experience for students – both women and men. This improved learning experience fosters the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills, and allows for practical learning beyond the classroom that improves a graduate’s employability.

The TESCEA partnership is led by INASP (UK), working with Mzumbe University (Tanzania), University of Dodoma (Tanzania), Gulu University (Uganda), Uganda Martyrs University (Uganda), Association for Faculty Enrichment in Learning and Teaching (Kenya) and Ashoka East Africa (Kenya).

TESCEA is funded by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) as part of DFID’s SPHEIR (Strategic Partnerships for Higher Education Innovation and Reform) programme to support higher education transformation in focus countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

To learn more about TESCEA, click here.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post

Quite informative piece